There’s something about standing on a JamaicanThe term "Jamaican" encompasses the citizens of Jamaica and their descendants in the Jamaican diaspora, representing a d... hillside. Perhaps it’s in HanoverHanover is a parish located in the western part of Jamaica, known for its scenic landscapes and historic sites. It offer..., or Saint CatherineSaint Catherine is a parish located in the south-central region of Jamaica, known for its significant historical sites, ..., where the air carries the scent of pimento, the hills roll lazily into the horizon, and somewhere just beyond view, a church steeple rises above a cluster of rooftops. It’s a vision that arrests the imagination—a meeting place for history, landIn real estate, land is a foundational element that significantly impacts the value and potential of a property. It enco..., and faith, all interwoven like the threads of an old tapestry. In Jamaica, to speak of land is to speak of history; to speak of the church is to speak of resilience; to speak of home is to speak of God. And often, the three are inseparable.

The Ground Beneath: Historical Foundations of Jamaican Real Estate

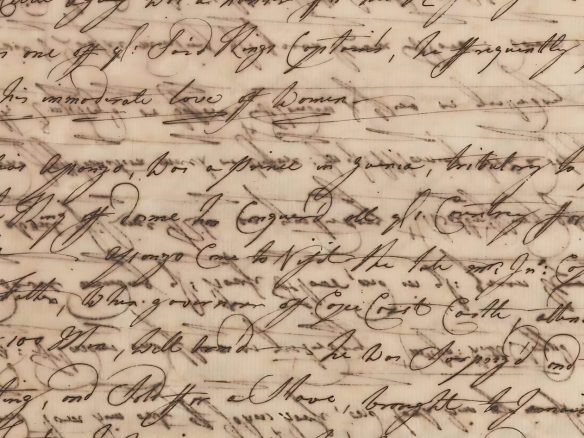

The story of land in JamaicaJamaica, with its vibrant culture and stunning landscapes, has a unique position in the global real estate market. The i... begins with colonial imprints. During the British colonial period, estates were sprawling and vast, dominated by sugar plantations, and controlled by absentee landlords whose wealth was built on the backs of enslaved peopleThe people of Jamaica embody a spirit that is at once richly diverse and unbreakably unified, as captured by the nationa.... Land was power, and power was the currency of society. The church, too, was not exempt—it often acted as both spiritual guide and landholder, collecting tithes and sometimes participating in the same economic structures that shaped society’s inequalities.

Then came emancipation in 1838, a seismic shift in both society and the landscape. Freed people needed homes, land, and communityIn Jamaica, "community" refers to more than just a geographic area; it embodies a collective identity rooted in shared e..., and missionaries—particularly Baptist leaders like Rev. James Phillippo—responded by purchasing land to establish the Free Villages. These were settlements designed for autonomy, where landownership could thrive alongside a spiritual community. In these villages, the church was the anchor, providing moral guidance, social cohesion, and, often, education. Land, faith, and social progress were literally and figuratively inseparable.

The church’s influence didn’t end there. By the late 19th century, many building societies, some church-led, allowed working-class JamaicansJamaicans are a resilient and vibrant people with a deep-rooted history defined by courage, resistance, and cultural ric... to save collectively, finance homes, and achieve ownership without reliance on distant banks. These initiatives were precursors to modern cooperative housing schemes, proving that faith and finance could coexist for community benefit.

Faith and Form: The Church as Guardian of Space

Fast forward to the present, and the church continues to shape the Jamaican landscape—physically, socially, and spiritually. Historic structures like Holy Trinity CathedralHoly Trinity Cathedral in Kingston, Jamaica, stands as a majestic testament to the island's religious and architectural ... in KingstonKingston, the capital city of Jamaica, embodies a dynamic fusion of historical depth and contemporary vitality. Establis... or St. JamesThe Parish History of St. James St. James, one of Jamaica's most historically rich parishes, has a legacy shaped by its ... ParishIn Jamaica, a parish is a unique blend of community, culture, and history. Each of the 14 parishes serves as a local gov... Church in Montego BayMontego Bay, often referred to as MoBay, is one of Jamaica's most popular tourist destinations, known for its stunning b... are more than places of worship; they are landmarks of community memory, testaments to architectural heritageHeritage, in the context of Jamaica, real estate, and the rest of the world, refers to the tangible and intangible asset..., and reminders of social evolution. The churches, often perched on hills or central town locations, quietly govern the rhythms of neighbourhood life.

Yet beyond bricks and mortar, the church has always been a community anchor. From education initiatives in colonial times to modern youth programmes and charitable efforts, churches have historically filled gaps where state infrastructure lagged. Even today, the congregation often doubles as a social safety net, offering guidance, gathering places, and occasionally financial support.

This dynamic is especially evident in the Free Villages, where church-led governance determined settlement patterns, lotIn Jamaican real estate parlance, the term "lot" refers to a parcel of land designated for residential, commercial, or a... allocations, and even local economic activity. The lesson is clear: in Jamaica, land is never just land; it’s heritage, faith, and community combined.

Land, Spirit, and Legacy

If there’s one thing Jamaica teaches about real estateReal estate refers to property consisting of land and the structures on it, such as buildings and homes. It also include..., it’s that land carries memory. Owning a plot is rarely just about investment"Investment" in the realm of real estate refers to the allocation of money or resources into property with the expectati...; it’s about roots, ancestry, and responsibility. Many families still live on lands traced back to Free Village allocations or church-led settlements. To build on these plots is to participate in a continuum of generational stewardship.

Faith adds another layer. Theologically, many Jamaican traditions see home and land as blessings and responsibilities—a canvas for human care under divine oversight. Metaphors of “building your houseA house serves as a fundamental structure designed for residential living, providing shelter and a place for individuals... on the rock” are not just poetic; they are deeply practical, reminding us that foundations—moral, spiritual, or structural—matter. And if God were a developerIn Jamaican real estate, a developer is a person or company that creates new buildings or improves old ones. They handle...? One imagines strict guidelines: sound foundations, robust drainage, good neighbors, and a sprinkling of patience for delays—advice that works as well in real estateIn Jamaican real estate, an estate refers to the total collection of assets and property owned by an individual, especia... as it does in life.

Contemporary Challenges and Opportunities

Today, Jamaica’s real estate market is vibrant, dynamic, and, at times, unforgiving. Urban expansion, coastal developmentIn Jamaica, the term "development" can refer to various contexts, each with its unique focus and implications. Real esta..., and foreign investmentForeign investment means when people, companies, or even governments from one country spend money to buy or build things... bring opportunity, but they also riskA risk is the possibility of an adverse outcome or loss arising from uncertainty or potential hazards. It represents the... erasing history, displacing communities, and undermining heritage sites. Many historic churches face pressures from urban sprawlUrban sprawl in Jamaica describes the expansion of urban areas into previously rural or undeveloped land. This phenomeno... or tourismTourism in Jamaica refers to the industry focused on attracting visitors to the island, who come to experience its natur... development, and not all congregations have the resources to preserve them.

TitleA title is a crucial document that establishes legal ownership of a property. When a buyer agrees to purchase real estat... disputes and unclear tenureIn Jamaican property law, "tenure" refers to the way in which land or property is held or occupied, defining the rights ... remain persistent challenges in rural or peri-urban areas, echoing centuries-old patterns of inequity. Here again, the church can play a mediating role, guiding cooperative solutions, championing community land trusts, and providing organizational structure for equitable development.

Financial accessibilityAccessibility in Jamaican real estate refers to the design and adaptation of homes and buildings to ensure that individu... is another hurdle. Modern banks can be selective or restrictive, especially for first-time homebuyers or small-scale developers. Drawing inspiration from 19th-century church-led building societies, cooperative finance models could empower communities, combining ethical oversight with practical resource pooling.

And, of course, there’s climate to contend with. HurricanesHurricanes, powerful tropical storms characterized by strong winds and heavy rains, significantly impact both Jamaica an..., earthquakesEarthquakes, natural events caused by the sudden release of energy in the Earth's crust, can have significant impacts on..., and coastal erosion make resilience not optional. Homes and settlements must be well-planned, sturdy, and adaptive, and lessons from history—like the rebuilding of Holy Trinity CathedralA cathedral represents a grand and historically significant place of worship, often serving as the principal church with... after the 1907 earthquake—remain relevant today.

Blending History, Faith, and Design

What if development were approached with the same artistry and care as the island’s historic churches? Imagine a new community built with aesthetic respect, social cohesion, and environmental awareness, inspired by the past but fully contemporary. Roads would follow natural contoursContours refer to the lines that trace the elevation changes of a land surface, mapping the varying heights across a lan..., drainage systems would anticipate storms, and homes would respect the land’s heritage.

Faith could guide the ethics of development, ensuring that economic ambition doesn’t overshadow communal good. Churches or community trusts could facilitate cooperative home ownership, restore historic structures, or act as cultural stewards. In this vision, development is not merely about profit but about storytelling, continuity, and rootedness—a tangible expression of the same values that built Jamaica’s Free Villages and historic church settlements.

Lessons from the Past, Visions for the Future

Jamaican real estateJamaican real estate encompasses a diverse property market within Jamaica, including residential homes, commercial build... is more than propertyProperty encompasses a wide range of tangible assets that individuals or entities can own, utilize, or invest in, includ.... It’s history underfoot, faith overhead, and community alive in between. The church’s legacyLegacy, in the context of Jamaica, real estate, and the broader world, represents the enduring impact of past actions, a... teaches that land is never neutral: it embodies struggles for freedom, moral stewardship, and social cohesion. Modern developers, investors, and communities would do well to heed these lessons: to build not just houses, but homes; to preserve history while embracing progress; to consider spiritual and social dimensions alongside economic ones.

Even a small smile enters the picture here. A well-meaning God might insist on sturdy foundations and a little patience, reminding us that good design—architectural, social, or spiritual—is never rushed. In Jamaica, as anywhere, the best projectsA project or projects, within the Jamaican context, refers to a planned endeavor undertaken to achieve specific goals or... are those that honor place, people, and purpose simultaneously.

So whether you are gazing at a colonial church, walking through a Free Village settlement, or evaluating a modern housing development, remember this: in Jamaica, land, faith, and community are inseparable. Real estate is more than square footageIn real estate, square footage refers to the measurement of livable space within a property, which plays a critical role...; it is heritage, stewardship, and an ongoing conversation with history—and perhaps, if you listen carefully, with God.

DisclaimerA disclaimer is a statement that serves to limit or exclude liability, usually found in legal documents, websites, produ...: This article is for informational and cultural exploration purposes only. It draws on historical records, social commentary, and present-day observations to reflect on the intersections of real estate, the church, and faith in Jamaica. It is not intended as legal, financial, or theological advice. Readers should consult appropriate professionals for guidance on real estate matters, legal obligations, or spiritual direction.

Join The Discussion