Editor’s Note (Journal)

This article forms part of the Jamaica HomesJamaica Homes is a premier real estate company offering a comprehensive platform for buying, selling, and renting proper... Journal, where we examine housing, landIn real estate, land is a foundational element that significantly impacts the value and potential of a property. It enco..., and developmentIn Jamaica, the term "development" can refer to various contexts, each with its unique focus and implications. Real esta... through a considered, long-form lens. Rather than reporting news, the Journal creates space for professional reflection, critique, and context — especially on issues that sit at the intersection of constructionConstruction is the dynamic process of designing and erecting buildings and infrastructure, crucial for shaping modern l..., planningPlanning in Jamaica involves managing land, resources, and infrastructure to support economic growth, social development..., climate resilience, and real estate in JamaicaReal estate in Jamaica refers to the buying, selling, leasing, and development of properties on the island, encompassing....

The piece below responds to a recent public commentary by our founder, not to restate it, but to interrogate the ideas it raises and extend the conversation for readers who care about standards, long-term outcomes, and the future of housing on the island.

Critique Article

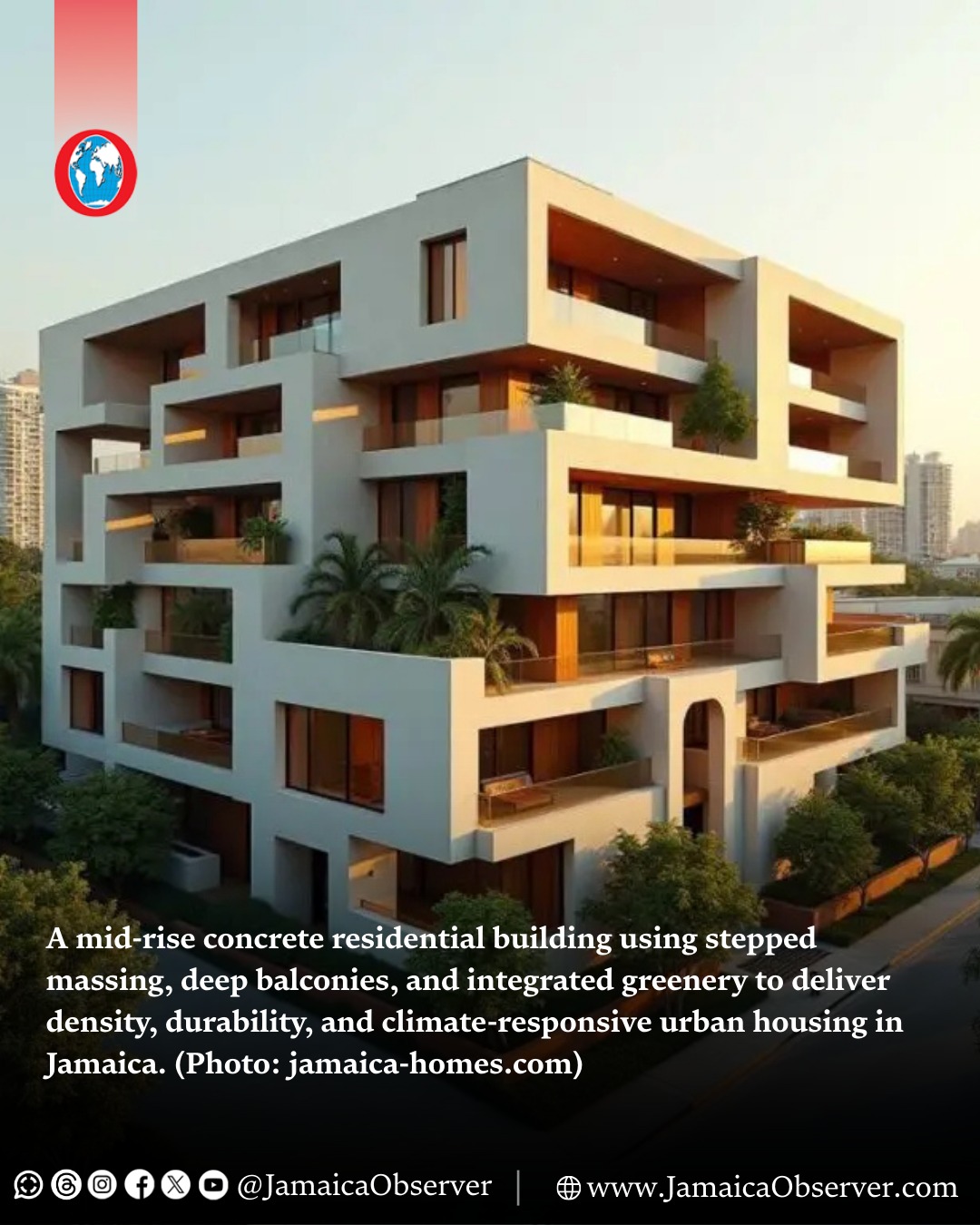

Every few years, JamaicaJamaica, with its vibrant culture and stunning landscapes, has a unique position in the global real estate market. The i... revisits the same uncomfortable question: how do we houseA house serves as a fundamental structure designed for residential living, providing shelter and a place for individuals... peopleThe people of Jamaica embody a spirit that is at once richly diverse and unbreakably unified, as captured by the nationa... affordably, safely, and at scaleScale is a fundamental concept in cartography that translates the vastness of the real world into manageable proportions... — without creating tomorrow’s crisis in the process?

In his recent Jamaica Observer article, “Container homes: Reckless shortcut or miracle cure?”, our founder Dean JonesDean Jones is a chartered builder, project manager, licensed real estate professional and the founder of Jamaica Homes, ... steps deliberately into that tension. Rather than choosing a side, the article does something more difficult: it asks Jamaica to slow down, think clearly, and separate emotion from engineering.

(You can read the original article here: https://www.jamaicaobserver.com/2025/12/28/container-homes-reckless-shortcut-miracle-cure/)

That framingFraming is a fundamental phase in the construction of a building, focusing on creating the structural framework that sup... is the article’s greatest strength — and also the point where further scrutiny is useful.

A needed intervention in a polarised debate

Jones correctly identifies the false binary that dominates public discussion. Container homes are routinely presented as either a dangerous shortcut or a silver bullet for Jamaica’s housing shortage. In reality, neither position survives serious technical examination.

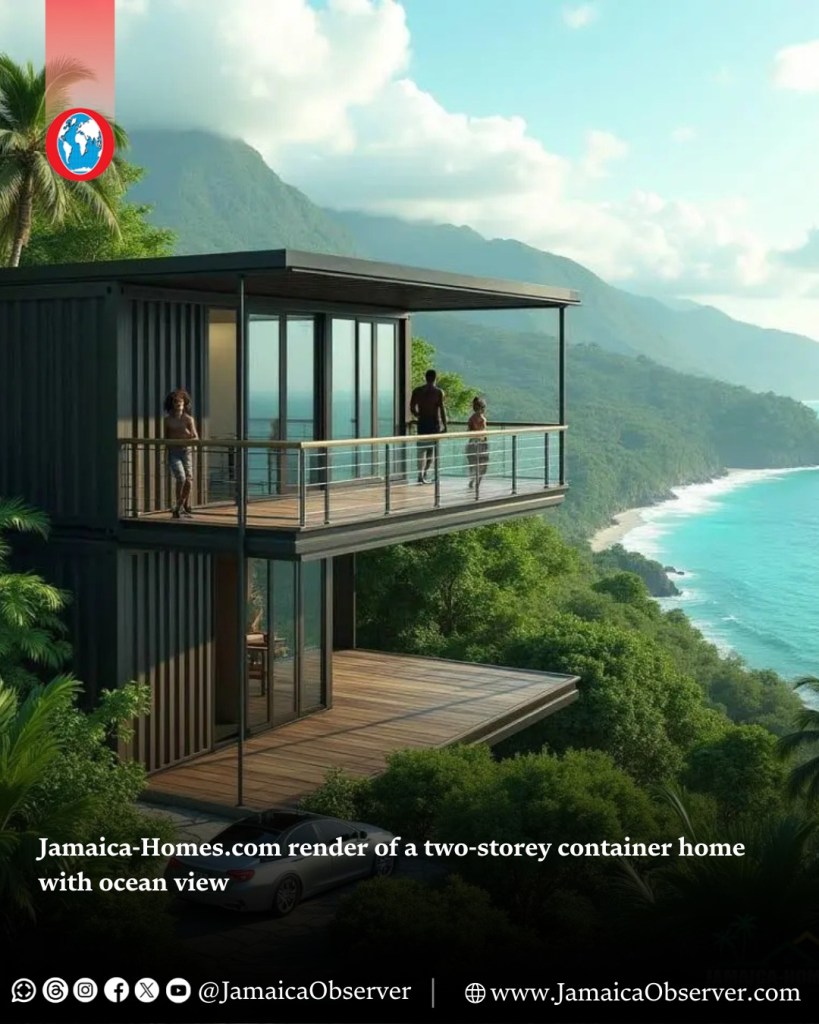

The article is at its most persuasive when it grounds the debate in Jamaica’s environmental reality: heat, humidity, salt air, hurricanesHurricanes, powerful tropical storms characterized by strong winds and heavy rains, significantly impact both Jamaica an..., seismic activity, and climate volatility. These are not abstract risks. They are daily designDesign is the art and science of creating plans and specifications for the construction of objects, structures, and syst... constraints. Any housing solution — concrete, timber, steel, or hybrid — that ignores them willIn Jamaica, a will is a legal document created by an individual to specify how their assets, including their belongings ... fail.

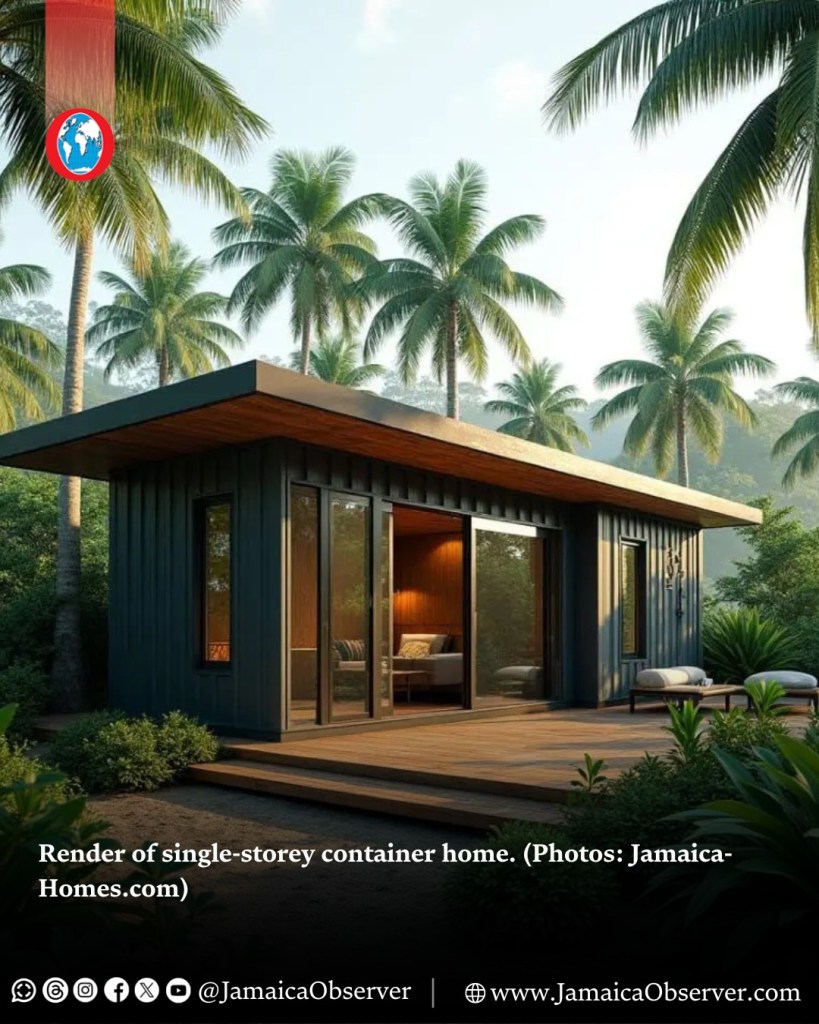

By reframing container homes as a system rather than an idea, the article cuts through a great deal of noise. A shipping container is not housing; it is a structural component. What matters is specification, treatment, insulationIn Jamaican real estate, insulation refers to materials and techniques used to enhance a building's energy efficiency by..., ventilation, anchoring, and long-term maintenance. On this point, the argument is technically sound.

Where the article is strongest

The comparison with post-war prefabrication in Britain is particularly effective. It reminds readers that housing failures rarely come from innovation itself, but from rushed implementation, poor standards, and political expediency. Jamaica has its own version of this history in poorly planned schemes that looked affordable upfront but became expensive to repair, retrofit, or abandon.

Another strength is the refusal to romanticise container homes. Jones is explicit: they are not the solution. They are one possible tool. That restraint matters. Jamaica’s housing crisis is too complex for single-answer thinking, and the article avoids that trap.

The emphasis on dignity is also important. For families living under compromised roofs, material debates are secondary to safety and stability. However, the article is careful not to use urgency as an excuse for lowering standards — a line too often crossed in post-disaster construction.

Where the debate still needs sharpening

Where the article could go further is in addressing governance and enforcement, not just design quality.

Saying “container homes work if done properly” is true — but incomplete. Jamaica’s real challenge is not the absence of good ideas; it is the uneven application of standards. Poor construction outcomes in Jamaica are rarely caused by materials alone. They are caused by weak oversight, inconsistent inspections, informal builds, and cost-cutting under pressure.

A well-designed container home on paper does not guarantee a well-built container home on site. Without clear national guidelines, certification pathways, and inspection protocols specific to container and hybrid structures, the riskA risk is the possibility of an adverse outcome or loss arising from uncertainty or potential hazards. It represents the... is not theoretical. It is systemic.

In other words, the danger is not that JamaicansJamaicans are a resilient and vibrant people with a deep-rooted history defined by courage, resistance, and cultural ric... will build container homes — it is that they will build bad ones repeatedly, and at scale.

The land question beneath the surface

One subtle but important dimension sits just beneath the article’s surface: land useLand use in the context of real estate in Jamaica refers to how different parcels of land are utilized and designated fo....

Container homes are often discussed as mobile, temporary, or flexible. But in Jamaica, housing quickly becomes permanent — legally, socially, and emotionally. Once placed on land, a container home is no longer an experiment; it becomes part of the built environment, affecting neighbouring values, infrastructure loads, drainage, and planning norms.

That means the container home debate is also a planning and real estateReal estate refers to property consisting of land and the structures on it, such as buildings and homes. It also include... conversation, not just a construction one. How these structures are zoned, valued, insured, financed, and transferred over time matters just as much as how they are built.

A fair and necessary contribution

Overall, the article succeeds because it does not pretend the answer is simple. It respects professional caution without surrendering to fear. It challenges blanket rejection without promoting shortcuts. And it insists — correctly — that Jamaica is capable of building better than its worst examples.

The real takeaway is not that container homes are good or bad. It is that standards are everything. Poor standards will fail in block-and-steel just as surely as they will fail in steel boxes.

As Jamaica searches for housing solutions that are resilient, affordable, and dignified, this article is a useful reset. It reminds us that materials do not create crises — decisions do.

The next step is ensuring that innovation is matched by regulation, enforcement, and long-term thinking. Without that, any housing “solution” risks becoming the next problem we inherit.

Join The Discussion